What Did We Do?

Why Scoop and the Jigna Vora story are personal for me, and the lessons I learned from the injustice that Jigna endured

I started watching Scoop on Netflix on Friday night. I am still not done with it, but the first few minutes of the first episode itself triggered a flood of memories and emotions that I have been processing ever since.

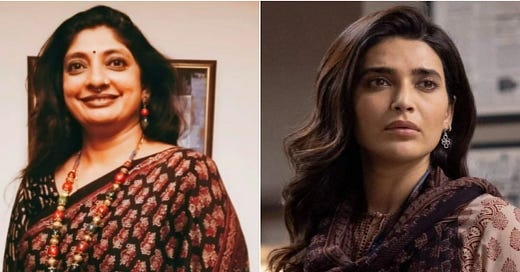

The series tells the true story of Jigna Vora, a journalist who was arrested in 2011 in connection with the murder of J Dey, a veteran crime reporter, shot dead a few months earlier in Powai. Jigna was with The Asian Age at the time, and so was I. Her story is inextricably linked with mine in a way that shaped a lot of my opinions about policing and journalism. And if there is one thing I learned during those formative years of my career, it is that journalists can be the most vicious when they want to be.

I used to sit right in front of Jigna at the time, separated only by a partition. I was still a rookie – I’d only started my journalistic career at The Asian Age – my first job – in 2008 and promoted from Trainee Reporter to Staff Reporter in 2009. Three years is nothing in any profession, more so in journalism, where just having good sources does not ensure a roaring career. Your sources are government servants who can get transferred anywhere in the state and hence, your true skill depends on more than just getting pally with a few cops.

I was on my way to office after an assignment on a particularly rainy evening when news about Dey being shot dead came in. I turned around, re-entered Elphinstone Road railway station – now Prabhadevi – that I had just come out of, and rushed to the hospital where he had been taken. Unfortunately, we lost him that evening.

In the months to come, we’d hear many theories as to the motive behind his killing. A particularly wild one, offered by none other than the then police commissioner, Arup Patnaik, was that the red sanders mafia was behind his murder. It would have been funny, had it not been so sad.

None of us, however, were prepared for one of our own to be declared a suspect. There were whispers, of course, long before the official declaration came. And when it did come, it came in the form of a front page story in a leading tabloid. It didn’t name Jigna, it just said a lady journalist was the ‘prime suspect’ in the investigation. But the way the story was written left no doubt as to who the lady journalist was.

At the Asian Age, it was like a nuclear bomb had exploded, and all of us were walking around dazed by the radiation. There were uncomfortable silences and whispered conversations across the newsroom. I was too small in the scheme of things to matter, or to even ask anyone what was happening.

But this same lack of seniority also gave me a crucial advantage outside the office. Because of my low stature, I didn’t have much to say, so I listened.

Journalists, as a lot, love to boast. In some cases, it is ego; in other cases, it is a daily battle to keep your self esteem intact in a world where you are only as good as the last story that appeared with your name under the headline.

When I entered the Mumbai Police headquarters that afternoon, a particularly self-important journalist accosted me right near the gate and, without preamble, asked, “Nikaal diya na usko?” I didn’t need to ask who he was referring to.

Coolly, or as coolly I could, I said, no, Jigna was very much an employee of The Asian Age.

“She won’t be for long,” he snickered and I walked away. Next, I met a senior journalist with a leading broadsheet daily. I asked him what he thought and his response was something on these lines: “When a person makes too much progress too fast, you can expect them to come crashing down.”

I think it was at that point that I began to realize what the main issue was. Jigna didn’t have many friends. A lot of people, be it reporters or police officers, hated her guts. Particularly reporters were jealous of the stories she would get, and especially irritated at the fact that she managed to get them despite working for a relatively smaller brand, while they had big brand names printed on their visiting cards. Few things are as intoxicated as a mediocre journalist being able to tell the world that they work for the biggest brand in journalism. Not getting the stories to match that ego can hurt really, really badly. I’m not even going to get into the misogynistic conversations that every man starts about a woman getting ahead in her career by doing ‘favours’.

My belief about Jigna and her lack of friends only went on to become stronger as the days passed. Every day, reporters would gather in the Press Room at the headquarters and talk about how her arrest was imminent.

“She’ll be arrested in a couple of days.”

“You don’t know what you’re talking about. The arrest is happening tomorrow.”

“My source says she might be picked up tonight itself.”

Despite all the talk, which let us know that an arrest was surely coming, when it did come, it still shocked us all. Without warning, the Crime Branch turned up at her house and took her away one morning. And even before this was fully done, officials confirmed to journalists that she had been arrested. Wires and TV channels had broken the story even before the police team reached the Crime Branch headquarters with her.

The arrest only intensified the sentiment against her. While covering such an important development in a big ongoing story was unavoidable, some news organizations were particularly ruthless in their coverage. Scores of my counterparts called me up to ask if I had a picture of Jigna that they could run with their story. It got so bad that I stopped taking their calls for a while.

A few reporters had already downloaded an old picture of hers from her social media profiles. Jigna had had the sense to delete her profiles when the first article about her came out, but some journalists had saved her picture even before that.

In the days to come, a few newspapers and TV channels put out daily updates, including supposed details of her interrogation, how she ostensibly ‘broke down and confessed while crying’ and many such stories. It took me a while to realize that the footsoldiers weren’t the only ones to blame; their bosses wanted follow up stories daily. The orders were coming straight from the top.

When they weren’t busy writing about her, they were dishing out advice.

“Get out of that place,” one of them told me, referring to The Asian Age. “Don’t waste your life there.”

I shall always hold my head high about the fact that I didn’t jump ship. I stayed till the Resident Editor, Mr S. Hussain Zaidi, was asked to leave and after even after that. It was only around a year later that I applied to the Indian Express when I heard of a vacancy there, and was selected.

Mr Zaidi’s exit was a personal blow for me; I cried like a child in front of everyone that evening before running out into the verandah. It only took a day for the rumour mills to start talking about how he was shown the door because he stood by Jigna. He had given a soundbyte to news channels saying that Jigna is a journalist of impeccable integrity. The wise minds put two and two together within two seconds. None of these expert analysts knew that the instruction to give that soundbyte had come directly from Hyderabad, where Deccan Chronicle, Asian Age’s parent company, is headquartered. But not knowing the whole facts has never stopped the self-proclaimed wise men from forming opinions.

The onslaught against Jigna in the form of ‘news’ stories continued for months, till the chargesheet was filed and for some weeks after that as well. A crime reporter wrote a first-person account of ‘the Jigna she knew’; something you’d normally associate with the deceased. On the day that the verdict was to be announced, a front-page story in a newspaper talked about how she might face the death penalty if convicted.

And then, she was acquitted of all charges and finally came home to her family. Was I surprised? Not in the least. Within a few months of her arrest, it had become amply clear that her supposed link to the case was tenuous at best. And this is something that almost every crime reporter knew, but this didn’t stop them from writing.

The same journalists went gaga over the verdict, but if Jigna was expecting dignity in that coverage, she was to be, once again, disappointed. The same tabloid that had broken the story about her being a suspect sent a photographer to her house to try and get a picture, despite Jigna having made it clear she did not want to be photographed or interviewed.

Meanwhile, I ran into the same senior journalists who had advised me to not ‘waste my life’ at the Asian Age at the same Mumbai Police headquarters. This time, they were talking about how ‘none of us stood by her in time of crisis.’ I kept my mouth shut; it was all I could do to not burst out laughing.

They did have a point, though. As someone I respect very succinctly put it, “When Dey sir was killed, we all marched to the Mantralaya. When Jigna was arrested, what did we do?”